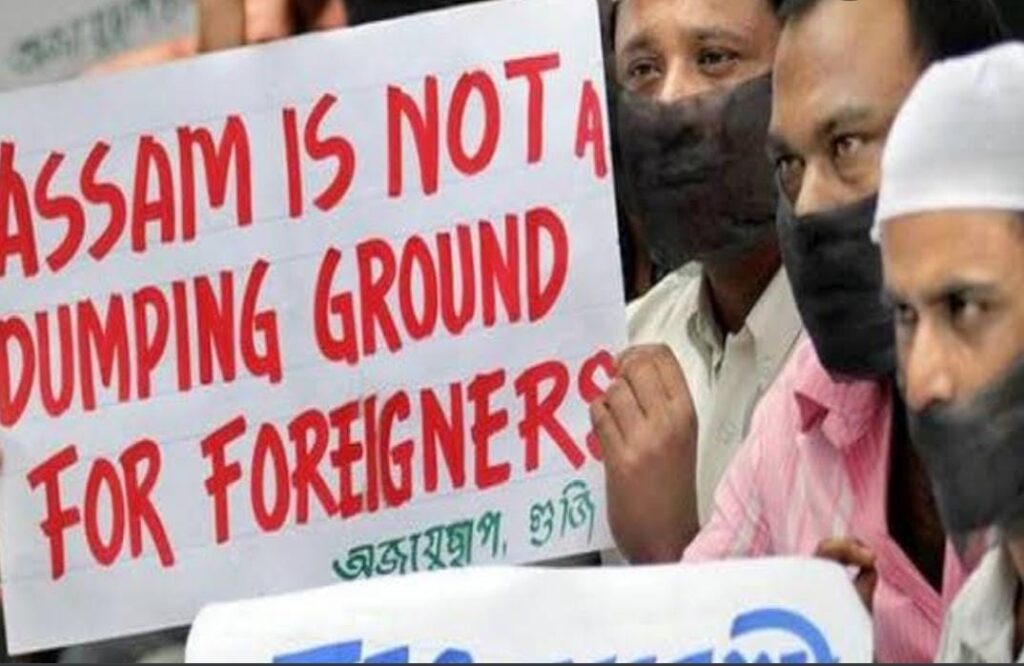

The Citizenship (Amendment) Bill, 2019 came into force on 10 January 2020 (Signed by the President of India on 12 December 2019). It was during those days that Assam saw another violent uprising against the said Bill. Although the central and state governments promised that there was no need to worry, the people of Assam were worried still; they might be facing a threat to their identity all over again after almost 35 years. It seemed like history was repeating itself but this time the uprising was spontaneous. People from different educational institutions, workplaces and organizations came out to the streets in thousands protesting the Bill even though it was bound to be enacted given that the Government had a clear majority. The ask for the people of Assam, unlike the rest of the country, was very clear – any kind of migration would surely pose a cultural threat to the people of Assam who were already facing the menaces of having illegal immigrants, therefore nothing could be accepted that led to such a scenario.

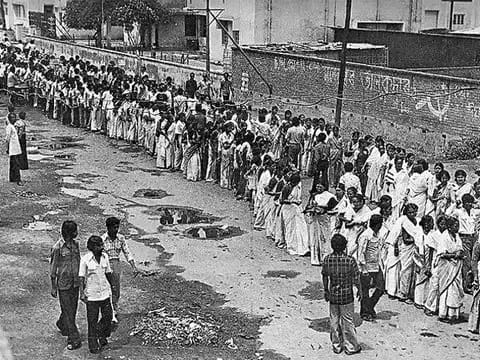

Back in the 1830s, the East India Company found out that tea could be a vital source of wealth for the company. To work in those gardens, the company brought people of tribal origins from central India. As Assam came under the Bengal Presidency and Calcutta had the most skilled workers, Bengali people were brought in to manage the ventures of the company. However, over time the Bengali language overshadowed the Assamese language and there was a virtual monopoly of the Bengali speaking community in all government offices resulting in a decline of Assamese people being employed. Meanwhile, there was also a serious upsize in the population of Assam and it did not concur with the statistical prediction of the natural birth rate, thereby pointing to immigration. Although after the Language Movement, the Assamese language was confirmed as the official language, the threat of immigration remained. That unrest among the people and the addition of non-citizens in the electoral roll of 1979 by-elections sparked the flames of the Assam Movement (1979-85). The agitators of the movement demanded the Government of India detect, disenfranchise and deport illegal Bangladeshi immigrants. After mass civil disobedience, picketing, strikes and sacrifice of 855 lives (official Assam Government data), the Rajiv Gandhi government was forced to sign the Assam Accord.

Is the Assam Movement relevant after all these years?

According to the Assam Accord, the Government of India agreed to secure international borders against infiltration by the erection of walls, fences and barbed wire barriers along the border with strict patrolling by security forces. To aid this the government also agreed to construct roads along the border. Monetary compensation to the families of the martyrs and opening of a refinery, reopening of paper mills and setting up educational institutions, all formed part of the agenda. While IIT Guwahati and Numaligarh Refinery Limited were set up, Ashok Paper Mill which was supposed to be reopened in Jogighopa never really became functional. But the core issue that triggered the Assam Movement remains, unfortunately, unaddressed even today.

After the Assam Movement, some leaders of the movement formed the Assam Gana Parishad (AGP), to go on to win elections for forming the state government. Prafulla Kumar Mahanta, erstwhile President of AASU, became the Chief Minister. However, neither that government nor the succeeding governments properly looked into the migrant problem. Officially there are three road links from Bangladesh to India –

- Mankachar Land Customs Stations(India) and Rowmari post (Bangladesh)

- Karimganj–Beanibazar Upazila via Sutarkandi integrated check post crossing on NH37(India) and Sheola post (Bangladesh)

- Karimganj Steamer and Ferry Station (KSFS) Land Customs Stations(India) and Zakiganj post (Bangladesh)

But migration has not stopped. It is 12.2 Km from the Sutarkandi check-post to Karimganj town and 300 metres just across the Kushiyara river. Boatmen from both India and Bangladesh sail up and down the river. It is hard to detect who comes and goes where. Similar activity happens in the Mankachar region too. Occasionally some migrants are deported if caught committing some kind of crime but the numbers deported are far less than the influx.

Along with the Accord came the new Illegal Migrants (Determination by Tribunal) Act, 1983 which described a controversial procedure to detect illegal immigrants and their expulsion from Assam. The Act and its Rules were so bizarre that the Act itself could be deemed futile. By 2013, the Supreme Court of India passed an order to update the National Register of Citizens for Assam. It came with a ray of hope that finally, the people of Assam will get a solution to the illegal immigrants issue, now that the Apex court was monitoring closely with central agencies involved. The methodology was to publish the legacy data, that is the electoral roll of 1951 where people had to search for the name of their ancestors and once found they had to prove their relationship with the said person. If the ancestors’ name was not in the legacy data then a person could prove that he or his ancestor has been living in Assam from before 24 March (Midnight), 1971. It took six years to publish the final draft of the NRC on 31st August 2019 but left 1.9 million people out of it. The moment it was published, the NRC dived into controversy. A sitting MLA of the All India United Democratic Front expressed that a huge number of Hindu Bengali people were left out of the NRC and deemed as foreign nationals. Meanwhile, the Union Home Minister Amit Shah declared that the process of updating the NRC shall be exercised nationwide and Assam shall not be excluded. Seconding the declaration the then finance minister and now Chief Minister of Assam Dr Himanta Biswa Sharma said that the present NRC process should be scrapped and Assam shall be a part of the National NRC process directly implying a wastage of Rs 1600 crores of taxpayers money.

Naturally, after scrapping the NRC and passing the Citizenship (Amendment) Act, 2019, people speculated that a huge influx of Bangladeshi people into the state might happen and instigated a sense of fear and insecurity in the minds of the people. The Government, both central and state, were, however, fixated on the fact that only Hindu Bengalis who are facing persecution in the Muslim majority nations shall be brought back. But Assam’s concern was never communal. The problem was ethnic. The people feared a threat to the Assamese culture and it remains the same whether the migrants are Hindus or Muslims.

Even after 35 years of the Assam movement, Assam’s migrant problems remain unsolved. The threat to culture continues to persist. As time passes it will be harder to detect who were the indigenous citizens and who migrated. With the passing of the Bill to become a law, we can only be hopeful that the migrants slowly but surely get assimilated into the Assamese culture; without posing any threat. However, the basic questions remain – Will illegal immigration ever stop and would Assam be able to uphold its ethnicity while bearing the burden of all immigrants (including the now legal immigrants under the Act)?